Libušín sits on a mountain pass in the Czech Republic's Moravian-Silesian Beskids, looking like something out of a Brothers Grimm tale. This isn't some modern Alpine resort masquerading as traditional – it's the real deal, a wooden lodge dripping with hand-carved details and Art Nouveau flourishes that somehow manages to be both a museum piece and a functioning hotel.

The dining room alone, with its cobalt blue walls and mythological murals, seats 200 people. When fire tore through the building in 2014, destroying its most precious spaces, the question wasn't whether to rebuild – it was whether anyone could.

Getting There

Libušín sits at Pustevny Pass, roughly an hour from Ostrava and two from Brno/Katowice. The pass takes its name from the hermits who lived here until 1874. You can drive the winding mountain road (genuinely hair-raising, according to those who've attempted it), but the better option is the chairlift from Trojanovice.

This isn't just any chairlift – it's the first one ever built in Europe, installed in a brutal 1940 winter when temperatures hit minus 30 Celsius. The ten-minute ride covers 1,737 meters and climbs 400 meters in elevation. Modern renovations have replaced the original supports, but the route remains the same.

A Slovak Architect's Slavic Dream

Slovak architect Dušan Jurkovič designed Libušín and its companion building Maměnka in 1897, completing them two years later for the Pohorská Jednota Radhošť hiking club. The project cost 82,433 Austrian crowns – a fortune at the time. Jurkovič had studied architecture in Vienna but spent his free time watching local carpenters work, even apprenticing with them. His style, known as folk Art Nouveau, pulls from Moravian, Wallachian, and Slovak traditions while nodding to the English Arts and Crafts movement.

The buildings are riotous compositions of carved wood, lace-like roof edges, and half-timbered walls. Libušín got its name from the Czech princess Libuše. Space was tight on the mountain pass – the lodge was squeezed between two other structures – so after World War I, they added living quarters upstairs and built a kitchen in the back wing.

During World War II, German tourist organization Kraft durch Freude tried to claim the buildings. They failed, but by war's end, Hungarian assistance units and Hitler Youth had trashed the place. When Jurkovič visited in 1947, months before his death, demolition seemed likely. He argued for preservation, and somehow the buildings survived, though they sat deteriorating until 1995 when the Wallachian Open Air Museum in Rožnov pod Radhoštěm took them over. Both structures were declared national cultural monuments that same year.

The 1996-1999 renovation cost 25 million crowns. Fifteen years later, on March 3, 2014, fire destroyed Libušín's right wing, including its spectacular dining room. Investigators eventually traced the cause to poorly installed stoves from a 2008 heating repair – an air pocket in the chimney system wasn't properly isolated from wooden walls and beams. Inspectors had missed it entirely.

Rebuilding from Memory

No original construction drawings existed. The restoration team had only photographs of the building's front. They started by cataloging every charred and salvaged beam in the rubble. Only 7% of the original wood could be reused. Trees were felled in fall 2016 and processed through winter using the same hand-crafting techniques from a century earlier.

The team built a 3D model of the interior, pre-assembled the timber frame in a workshop, then reconstructed it on site like a massive puzzle. They hand-finished all surfaces, mixed oil paints according to original recipes, and even hand-blew the glass. The reference point was 1925, when the lodge became fully operational after World War I. Historical photos from that year guided the color scheme.

The new version includes modern fire suppression systems throughout – thermal heat pumps replaced the old stoves, and a water system runs through the shingle roof to spray facades and surfaces. The dining room has an inert gas system normally used in museum archives; if activated, it lowers oxygen levels to stop combustion without damaging the irreplaceable interior. The whole building has fire sensors and voice alerts. In 2021, the restoration won an award from the director general of the National Heritage Institute.

Libušín reopened on July 30, 2020.

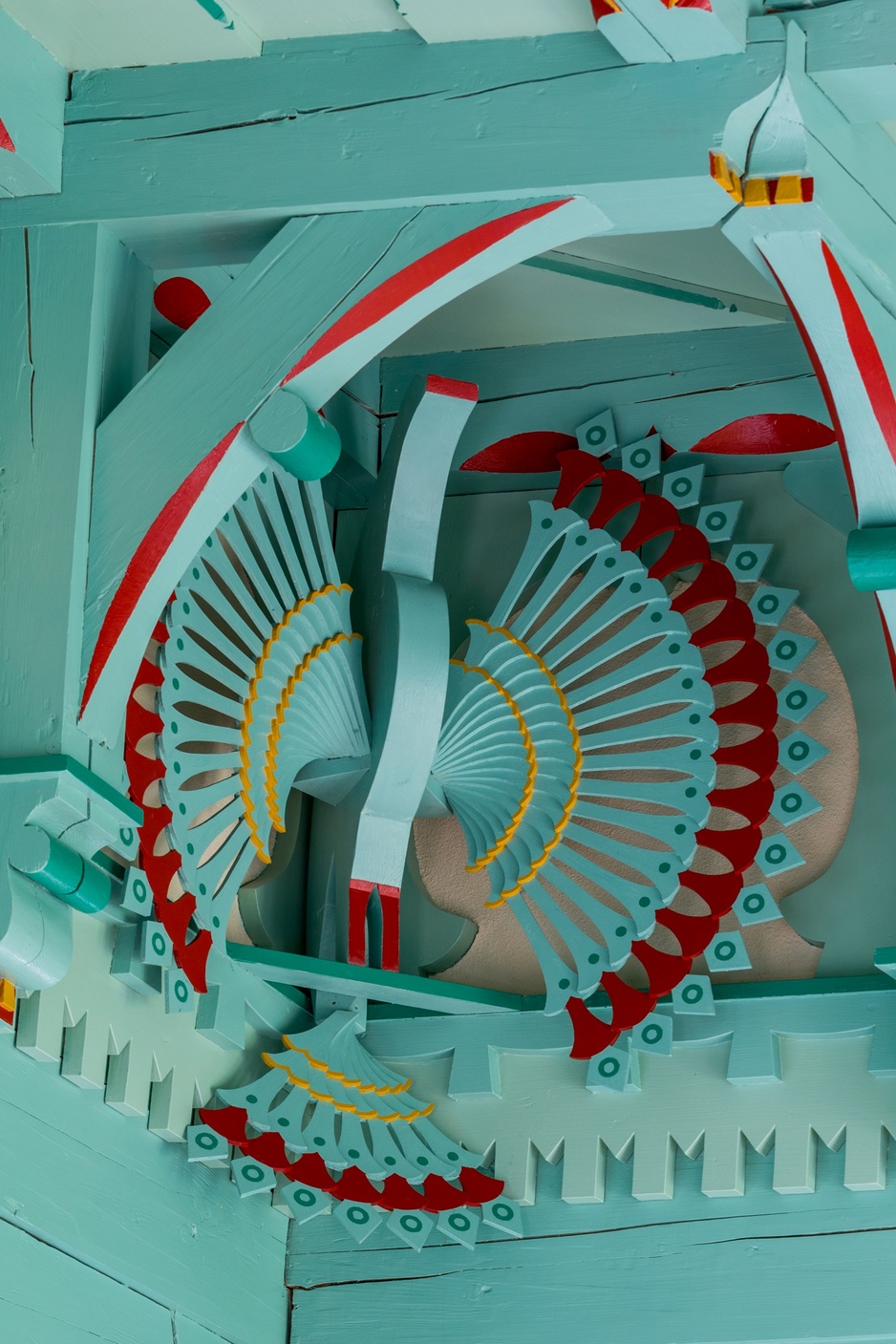

The Dining Room

The main dining hall is where Jurkovič's vision fully lands. Painter Karel Štapfer executed the murals based on drawings by Mikoláš Aleš, depicting the god Radegast, a doorkeeper named Stavinoha, two highwaymen, and Saint Wenceslas with his banner. Aleš took cues from Jan Matejko's historical paintings – his decorative work appears throughout Prague's public buildings, including the National Theatre. The 200-seat space mixes styles and explodes with color, a maximalist approach that somehow coheres into something both overwhelming and intimate.

The carved wooden details extend everywhere – balustrades, ceiling beams, window frames. Every surface seems to have some kind of ornamental treatment, whether painted pattern or relief carving.

The Rooms

Twin Room

Maměnka, the companion hotel, maintains the same architectural DNA but uses a different color palette. The rooms have warm tones and traditional pine furniture.

Double Room

Small touches appear throughout – patterned rugs, heart-shaped door decorations, even ornamental trash bins. It's simple but carefully considered. The fresh mountain air doesn't hurt either.

Double Room

Libušín also offers standard rooms with similar attention to traditional detail and craft.

Double Room

Deluxe Double Room

Suite

The real draw is the suite, which takes the folk Art Nouveau aesthetic to its fullest expression – more carved wood, more painted ornament, more of everything that makes these buildings feel like they emerged from some collective Slavic fever dream rather than an architect's drafting table.

The Suite's private terrace

756 57 Prostřední Bečva, Czechia